It might seem offensive that I could attempt to review a game with as much history and depth as Go. Perhaps it means that my ego is overinflated if I expect the weight of my word to mean something when talking about such a classic. Of course it’s a great game. History proves it’s a great game. Its culture and community proves it’s a great game. Yet here I am, shamelessly reviewing it.

But reviews are secretly not about whether a game is good or not. All games have an audience. Board game reviewers can harp on Monopoly all they want, yet more people find joy in that game than in most hobby games combined. At the end of the day, your experience playing is all that counts. And to that end, reviews are more about matching experiences to the players who will like them.

So what kind of experience is Go?

First, let’s start with the rules.

No one can say Go isn’t an elegant game. The rules take all of a minute to explain.

No one can say Go isn’t an elegant game. The rules take all of a minute to explain. Players take turns putting down a piece of their color, called a stone, one at a time on the intersections of a 19 by 19 grid. The stones, once placed, never move.

Stones that are fully surrounded are captured and removed from the board. And at the end of the game, you score points for every spot on the board that your stones surround and for each captured stone. Minus some specifics of capturing, a single rule about where you can’t place stones, and a single rules exception (the dreaded ko), that is all there is to the game.

But somehow, cross to any easy logic, the simplicity does not make this game simple to actually start playing. Beginners won’t even know how to score their games. They won’t notice their illegal moves. They won’t always notice when their stones are captured. They won’t even know where to begin with how to prioritize the most valuable spaces on the board, or even the kinds of moves that take territory.

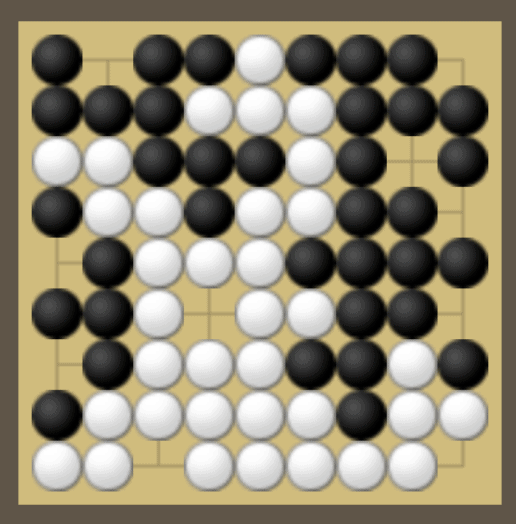

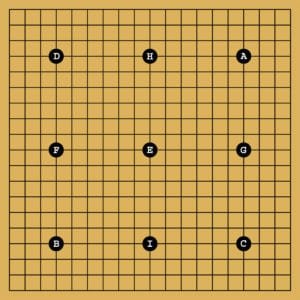

All in all, Go is complex enough that the game is taught in stages. First, a capturing game, where the goal is to be the first player to capture an opponent’s stone. Next, you play on a 9×9 board, as opposed to the full game which is played on 19×19. Then you may level up to one final intermediary step, the 13×13, or go straight into the full 19×19.

This experience can be fun, or miserable, depending on who is walking you through it. But know that capturing games are inherently flawed: once you get good at them, it starts to get tedious. But that’s the whole point of the exercise. You must struggle until it clicks, and you learn what you must learn from them. Until then, it may feel like bashing your head against a wall, or it might be some of the most fun you have with the game.

There is a saying in Go that sets the tone for the game as you begin: lose your first 100 games quickly. If you find that statement too discouraging, then Go probably isn’t going to click with you.

The way most gamers play games today is the opposite of how abstract strategy games have always been played. In Edo period Japan, gamers would dedicate their life to a single game, in hopes to join a shogunate sponsored school. These types of game schools exist to this day for the very same games, all around the world, to foster their professional scenes. Today, most gaming is unfocused by design: you play hundreds of games, some only once, others only a handful more times.

It makes sense that our priorities have changed in what we want from our games. In modern gaming, games have to be simple enough that you understand it in a game or two, but ideally you understand it after only a few turns. Most games getting published today will struggle to surprise you after ten plays, and that’s not a value judgement, it’s simply an analysis of their priorities.

But when you dedicate your entire life to a single game the opposite must be true: it must have secrets or it will grow boring. Even a game with a high skill ceiling that is unsurprising would become stale over time. But if a game can surprise you ten years later, there is something remarkable going on. Yet, Go isn’t just a game with enough secrets for ten years, or even a lifetime: it is a game with enough secrets that humans, 2500 years later, are still learning new and exciting things about the game continually.

For example, in Go, there is an idea called sente. It is the idea of being the initiator, of playing the moves that your opponent must respond to. While it has always been an important concept in Go, these days, professionals are willing to trade anything, including weak and undefended groups of stones, in order to keep it. This discovery is only a few years old, yet the way many people play has been completely upended by it.

Chess is a game that often feels limiting to me.

Tactics and strategy have a subtle difference, and that difference is anything but subtle in practice for these sorts of games. Tactics are the move-by-move plans, while strategy is the overall plan. Playing defensively is a strategy, moving a piece to the back row to keep your back rank defended from their rook is a tactic.

Abstract strategies are universally marked by having lots to chew on tactically. But I find the strategic viewpoint to be far more telling about a game.

In chess, there is very little variation in strategy: you must always fight to control the center, you must always play aggressively. If you fail to do any of these things over the course of a game, you will most likely lose. The strategy is a nearly a prescriptive set, with only minor variations between how you let it play out. Even when players do talk about other strategies, they are almost always talking about memorized opening sequences, and not their own moves.

Go, on the other hand, has what feels like an unlimited number of strategy options. You can play peacefully all game, or start a fight on your first turn that lasts all game. You can fight for the edges, or build territory in the center of the board by building long lines of stones around your opponents territory (a concept called influence or thickness). You can attack stones in order to kill them or in order to simply improve your own position. You can play a fast and loose game, leaving both players with more a complicated situation than they know how to deal with. Or you can play the most simple defensive responses only, forcing your opponent into a peaceful game. Honestly, the scope of the strategies in Go is staggering. Partly because of how strategically limited others games seem in comparison, and partly because every strategy actually works: from amateur level, to professional level, almost anything has merit to it.

But it’s not just how many strategies there are, it’s how creative they feel. It can feel like you’re an artist painting with stones when you execute an exceptionally beautiful plan that your opponent never saw coming. Sometimes, you’ll feel like a mastermind pulling off a heist that you had no business getting away with. Sometimes, you’ll do something that seems dumb, and you’ll shock even yourself with how permissive this game’s strategy is.

If chess is a battle, Go is the entire war.

The single most important mental exercise you’ll do during a game of Go is called reading ahead. That is the process of looking at the board, considering a move, imagining what your opponent’s response might be, how you might respond to that hypothetical response and so on. This is also primarily what you do in a game of chess, but there is actually a huge difference. While chess’s reading seems almost designed to make you feel dumb, giving you more than you can handle after imaging just a few moves, reading in Go could not be simpler. Even strong amateurs can read 50+ moves ahead in a game. That sounds ludicrous, but once you learn the shapes stones commonly make, it’s simply a matter of keeping those very simple patterns in your head. Even brand new players will find situations where they can imagine what the board might look like 20 moves ahead (for example, one of the first thing new players learn is how to identify a ladder).

And my point isn’t to brag about how big the numbers are in Go, just to say that the core thing that these games asks players to do is more enjoyable in Go. I find the whole process frustrating in chess, and people will tell you “that’s just part of the challenge.” And they’re not wrong, but it does feel like those players are missing the point of what a game actually is. Ultimately, I find what Go asks players to do to be much more enjoyable.

The game relies on far too much intuition for a player to rely solely on their ability to read. A common question you’ll ask yourself is “what is the most important point on the board? Which point scores me the most points?” And while on the surface, that sounds like a question that will be answered with a lot of counting, it usually isn’t. It’s almost pure intuition.

Everything about the game relies so heavily on intuition. For example, a single stone can completely change the nature of a fight maybe 14 spaces away from it. There is an interconnectedness between every stone on the board that no one will be able to explain to you coherently, but you’ll eventually learn to see it (perhaps some aspect of it at least). And that revelation will make the whole process of getting there worthwhile.

There are games that ask very little of its players, and give very little back in return. Go is not that game. Go asks for a lot, maybe it asks for more than any other game ever has, but it rewards you with a lot too.

The game becomes something zen, something that speaks to life in a beautiful & pedagogical way.

Something about this game makes its strategy advice sound like strangely zen life advice. For some people, this may be annoying. But for others, the game becomes something zen, something that speaks to life in a beautiful and pedagogical way. Go is a life style game, but it’s not just a game. It’s literally a framework to live your life by, sometimes more similar to religion than a board game. Even when playing it, it can feel more like you’re a monk assembling a mandala, than a game about war.

You could show me 100 Japanese proverbs mixed with Go proverbs, and I couldn’t pick out which ones are Go proverbs.

Guess which of these are Japanese proverbs about life and which are about Go:

- If you do not enter the tiger’s cave, you will not catch its cub.

- The enemy’s key point is yours too.

- There is luck in the last helping.

- One who chases after two hares won’t catch even one.

- Distant water won’t help to put out a fire close at hand.

- Make a fist before striking.

Answers

- Life Proverb: If you do not enter the tiger’s cave, you will not catch its cub.

- Go Proverb: The enemy’s key point is yours too.

- LifeProverb: There is luck in the last helping.

- LifeProverb: One who chases after two hares won’t catch even one.

- LifeProverb: Distant water won’t help to put out a fire close at hand.

- Go Proverb: Make a fist before striking.

The answers actually don’t matter, they could all be applied to both.

I’m not saying that you must play this game seeking life wisdom, or that its even normal to do so, but once you get deep enough into the rabbit hole, it almost seems inevitable that the game teaches you something about yourself, or the world. I keep mentioning this game’s secrets, and perhaps this is one of the most surprising ones.

One of the most common complaints about abstract strategies is the memorization. Chess gets a terrible rap for all the memorizing you must do: the best play sequences are not reasoned out, they are memorized, and you are a fool if you think you’ll find something better than what’s already out there. Frankly, memorization is a bad game mechanic. It’d be hard to argue that Go doesn’t ask you to do some memorization too. There are commonly played opening patterns that players have memorized, called joseki, but instructors discourage you from learning them until you become much stronger than a beginner. By the time they matter to your game, you’ll know the game well enough that you might shock yourself with how quickly you pick them up. Some joseki are even thrilling to learn, because the patterns are so surprising, or because they show you how to properly play in a shape similar to one you’ve tried to play before.

All in all, Go games are always novel. Every game feels so different, and has so many possibilities, and that insulates go from most of the memorization that chess players go through. Even joseki are frequently modified or ignored during real games. Joseki aren’t solutions to the opening game, they are a short truce that your opponent may choose to go along with or not.

Another common complaint is to lament how the more skilled player always wins. However, that is not true in Go. One of the most cleaver features of Go is its handicap system, where even an amateur can play an even game with a much stronger player. The weaker player simply begins the game with stones already on the board, one stone per difference in rank (for example, a 10 kyu player would get a 9 stone handicap against a 1 kyu player). This way, even big difference in skills can be mitigated in favor of a good game.

Of course, the bigger the gap, the less likely a 9 stone handicap will be enough to make the game even. But players rarely mind playing stronger players. Those are often the games they have the most to learn from. Games with vastly stronger players are called “teaching games,” and even getting trashed in those games can feel like a revelation, especially if you get to talk about the game after.

The arc of the game is always just as thrilling as any modern board game. One moment, your opponent is attacking you, yet you slyly see the opportunity for a counter attack. The next moment, the opponent is running from your counter attack, and you’re attacking the very stones that were your attackers a few turns ago. There is a push and pull of the game that can feel like as big a payoff, if not bigger, than any modern game.

The big question is, how much do you have to give? How much time do you want to spend studying and playing?

There is the perception that these games are simply a tool that smart people use to show off, and while that’s true, it’s obviously not all it is. There is absolutely a joy to find in this game, but perhaps much of it is gated for smart or very dedicated people.

If the halfway endless strategic possibilities of Go is exciting to you, then just know that you won’t find it any where else. If you think you’d love discovering just a tiny fraction of this game’s secrets, then I’d be willing to bet you will.

But before you get too excited about it, there is one big reason why I won’t recommend this game to most people, and its has nothing to do with the game itself. For any lifestyle game to thrive, community is essential. Without people to play against, you are missing out on so much of what makes the game great.

I read my first book about Go when I was maybe ten years old, and ever since, I’ve looking for someone to play this game with me regularly, and yet I never really found precisely what I was looking for. I recently found a few Go clubs to attend (the perks of living in New York City), but I don’t have anyone who I’d call a friend to play with.

Of course, online play is easy and ubiquitous. There are many different servers to play Go on, and some of them don’t even require an account to use. If you think you’d enjoy online play as your primary avenue of playing, then you really have nothing to lose by learning it.

OGS (Online Go Server) is one of the most popular, and easiest to use ways to play Go online. Lots of beginners to play against, and it regularly gets updates and new features. If you’re interested in Go, and you don’t have any local Go clubs, I recommend buying a Go board, playing capturing races with a friend, then playing games on OGS until you start winning them.

If you want to start learning the game, I’ve never seen a better introduction than the following book. It’s the first in a 5 book series. They’re all surprisingly quick reads, and they’re packed full with revelations.

Learn to Play Go: A Master’s Guide to the Ultimate Game (Volume I) by Janice Kim

I hope you can have as much fun with Go as I have.

Thanks for the well thought out, beginner-friendly review! I have found myself starting to look for a more rules-simplistic, elegant game than International Chess, and my family in my youth played a fair bit of Weiqi/Go around the coffee table.

Will pick up the Janice Kim book you recommended.

Just a spelling note for the Chinese tag (which is much appreciated!) – the Chinese spelling of Weiqi does not have a “U” in it. Hopefully this will help with online searches!

Thanks for writing a review on Go, it’s rare to see this being featured in a boardgaming blog. I do feel that you have dismissed the strategic depth of chess a bit too easily. I am a player of both games, and I have the deepest appreciation for Go, even more than chess, but to say that chess is nothing more than a fixed-strategy game with memorized opening patterns does not do justice to the game.

It’s not true that you always have to fight for the center, and be aggressive to win games. Those are important, but like many things, are just aspects of the overall picture. You can have control of the center, but if you have the worse minor pieces, undeveloped rooks, weak pawn structure, no King safety, then your center is not going to count for nuts. As for aggressive play, there are countless numbers of top players in the past and present that employed a passive style successfully. Ex-World Champions, Karpov and Petrosian excelled in quiet positions and were masters of prophylaxis: they made moves to stop enemy plans before they even thought of it, and then they slowly squeezed your space till you were suffocated and forced to concede a weakness. Current top players like Karjakin and Anish Giri are masters of defending and goading mistakes from opponents before pouncing. Even the current world champion, Magnus Carlsen does not have an aggressive style, he prefers to simplify the position without complications and then he can use his superior decision-making skill and endgame skill to beat his opponents.

Chess strategy do not only consist of fixed opening patterns that were memorized. In that aspect, it’s similar to Go as well. You can’t memorize a 3-3 invasion joseki and use that without considering the whole board position. Same in chess: you can’t memorize opening patterns and use it without understanding why and when it’s to be used. Even if you play it and somehow get an advantage out of the opening, if you don’t have the skill to convert it to a win during the middlegame and endgame, you are still going to lose.

Speaking of calculation, I can’t deny it’s a very concrete part of chess (as well as Go) , but it’s not simply calculating to the depths of your insanity to be able to play well. Grandmasters do not calculate 50 moves more than amateurs, they just simply know where to look and do not waste time calculating the wrong 50-move sequence. This is the intuition that you were referring to, it’s just obtained from seeing thousands of patterns that they can recall from their experience. I also believe that’s why it takes longer to reach a decent level in Go, there’s simply more patterns in Go to know than in chess. That also explains why chess and Go masters can beat amateurs seemingly without using time to think or calculate. Intuition like this plays a big part in both games, just like a Go master will tell me that this shape is not good for the upcoming fight, as well as a Chess Grandmaster will tell me that he feels this knight should be posted in a weird square for this position.

Everything you have said about Go strategy, I agree, and the same can be said about chess too. Fujisawa Hosai had a thick style and influence-oriented style, and Kasparov had a very dynamic style that preferred active pieces to material superiority. If there’s not enough depth in both games, such a wide variety of playstyles would not exist after hundreds of years, as everyone will just use the same one style that’s guaranteed to win.

Like you said, if there’s no secret to be revealed after years of play, then it’s not good enough. The chess world was shocked recently when AlphaZero showed us that chess can be played in such a radically different way and it still trounced the top players. The same happened for Go when AlphaGo was playing moves that completely befuddled Lee Sedol.

I get that what you were saying in this article were about the reasons you prefer Go to Chess and I respect that. I just wanted to put this out there to let you or your readers know that chess has its own inner beauty that can be enjoyed alongside Go. Both are excellent games that have survived centuries and millennia for a reason.